Richard Jones, Furniture Designer (UK)

Richard Jones is an amazing furniture designer and program leader of the BA (honors) Furniture Making at Leeds College of Art in the UK. He doesn’t only know how to work with wood but quite a bit about the material as well which he does some consulting on.

Key takeaways:

Fine craftsmanship takes time, sometimes up to 200 hours from sketch to finished piece!

Fine craftsmanship takes time, sometimes up to 200 hours from sketch to finished piece!- Finishing is an art that takes time and dedication… there are no shortcuts.

- Student interests at the start of a program evolve over the course of their study.

- Exhibitions can be a double edged sword. They can generate interest, but I’ve never found them to be a major source of work.

You can find him online at http://www.richardjonesfurniture.com… and be sure to checkout his gallery – lots of awesome designs and the photography is extremely well done!

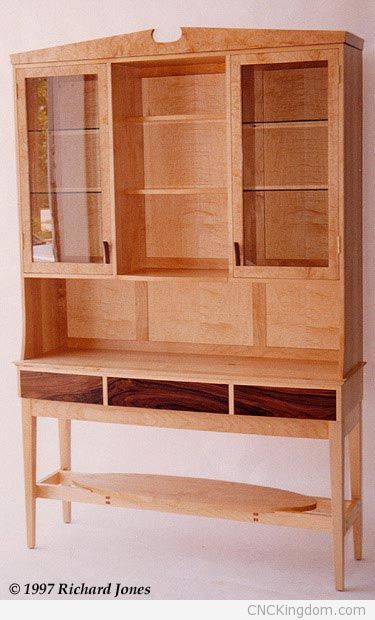

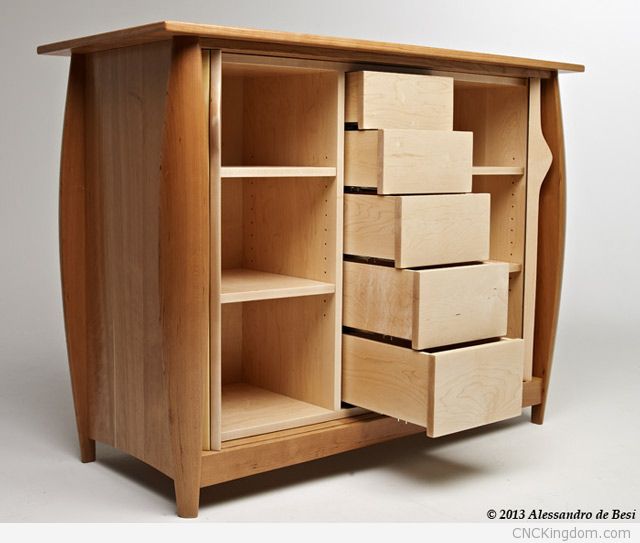

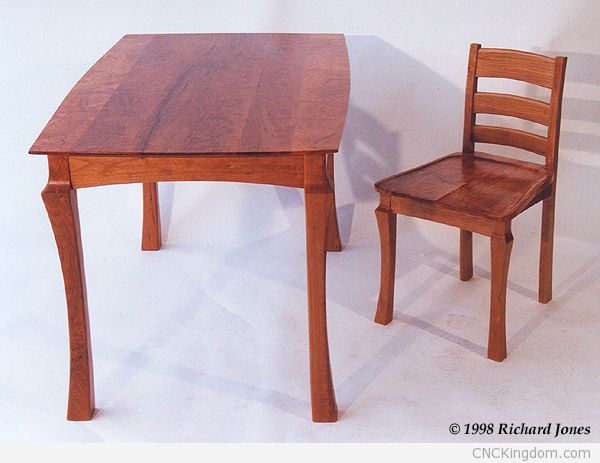

Richard, you have some awesome furniture – I’m especially fond of your Graduate Cabinet, Maple and Rosewood Dresser and your Torpedore. Where did the ideas for these pieces come from and how long does it take to plan and build these projects?

You have selected three pieces for comment that represent exhibition furniture I’ve designed and made. In each case therefore I could demonstrate to potential buyers and customers what can be done working in functional furniture items, but something that’s lifted above merely utilitarian, that’s distinctive yet not out of place in a person’s home surrounded by other styles.

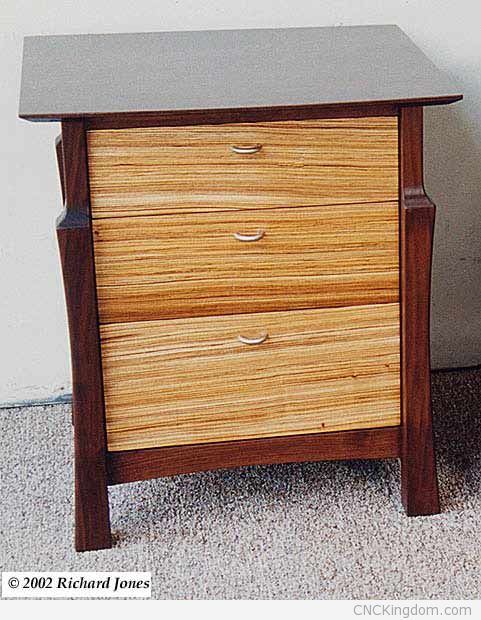

Graduate Cabinet came out of sketching variations of the traditional cabriole leg form, just for the enjoyment of playing with it, and one of my sketches produced this leg, or at least something very close to it which became the central motif for a hall table.

Graduate Cabinet came out of sketching variations of the traditional cabriole leg form, just for the enjoyment of playing with it, and one of my sketches produced this leg, or at least something very close to it which became the central motif for a hall table.

With an exhibition coming up I wanted to explore the use of this leg form again. After playing around with ideas in a sketch pad the idea for a cabinet with graduated drawers evolved.

Sweeps and curves in the legs are reflected in other elements of the cabinet, e.g., the drawer pulls are U shaped which picks up the sweep above the leg shoulder, and order imposed through the regimented drawer height incremental progression.

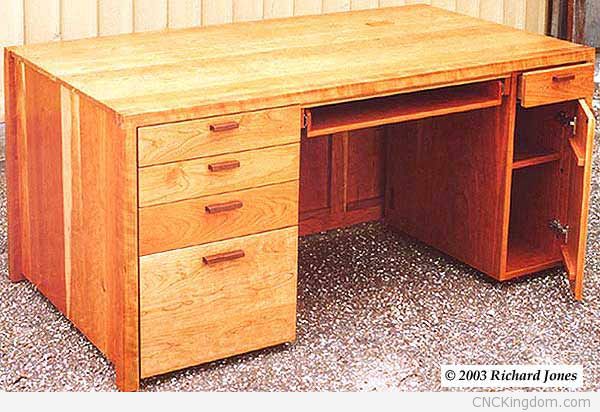

The maple and rosewood dresser evolved from an amalgamation of several traditional dressers, most of which tend to be ‘brown’.

The pale carcass was a small rebellion against the brown ‘conspiracy’ but with one nod to tradition being the horizontal brown band at the centre.

Torpedore was an exercise in making a visual statement with functionality a secondary consideration. Yes, the piece can store items, but its main purpose is to encourage the viewer to have a reaction of surprise, and hopefully cause them to smile… or more.

Typically, projects such as these take anywhere from about 120 hours to 200 hours from initial research and design development, through planning, to final execution.

How important is finishing in getting the “wow” factor from your clients and do you have any tips for somebody new to the industry on how to become a pro at it without spending years of their time learning how to do it properly?

Not every piece of furniture needs a high quality finish, with some pieces getting no finish at all, e.g., exterior furniture. However, most interior furniture does need a finish applied, and it’s not unusual in the craft furniture field for good quality prepping and finishing to take up 25- 30% of all the time allocated to making a piece. Beautifully constructed furniture can be spoilt completely by a poor finish. I’ve never heard of anyone that’s good at finishing that didn’t spend a great deal of time practicing the skills required.

Practical skills of any sort generally don’t fall into the ‘as easy as falling off a log’ bracket – there are no shortcuts I can think of in the field, except perhaps through sub-contracting the work to someone that already has the skills, and paying for it.

I can’t recall who said this, but it goes something along the lines of, ‘to become a master at anything requires 10,000 hours of research, study and practice’. There’s some truth in that.

What is it about woodworking that you enjoy so much about it? What types of wood are your favorite to work with and tools you enjoy using the most?

I like the challenge of taking pieces of this wonderful material, some of it staggeringly beautiful to begin with, and some that is pretty unprepossessing, but useful, and turning it into attractive and (usually) functional objects that can lift spirits. I don’t have a favourite wood; I just think each design and the location into which it’s going has appropriate wood choices.

As to favourite tools, perhaps the ones I wish had been around in the 1970s when I started are AutoCAD and CNC equipment. My skills in both are limited, but I like the way AutoCAD takes much of the drudgery out of creating orthographic projections through such abilities as being able to Mirror, Copy and Move objects around, and the ease of dimensioning. And CNC machines can do so much more than line bore to take hinges in kitchen cabinetry and the like; their ability to undertake complex work is phenomenal.

But I do still, after all these years, get great pleasure out of something basic like a hand plane that’s working like a dream – when the electricity fails I can still work wood, which is sometimes beyond those who can only work the stuff with such things as power tools, AutoCAD and CNC kit.

I like your Fettercairn Kirk Chair but it was designed by somebody else, what are some of the challenges present with trying to bring into reality another person ideas?

Having an understanding of what the designer was trying to convey, and sometimes diplomatically negotiating with the designer over practicalities, e.g., realising the design in a form that is within the budget.

You have extensive teaching experience in furniture making, what are some of the common misconceptions that students have before starting in your program? How fast does the typical student progress in ability over the course of the academic year?

I don’t think there are too many misconceptions in new students. Usually the student starts with a particular interest and preferred area of work, but this quite often evolves rapidly as they are exposed to ideas, concepts, ways of thinking, etc that are new to them.

For instance, a student may start with the ambition to just become proficient at practical furniture making whilst working within a limited palette of design styles that they like. Over the three year period they study on the course I run I have seen students go from this to become abidingly interested in research on the subject and into design disciplines, along with an inquisitiveness into the broader field Arts and intellectual rigour that is a far cry from becoming essentially just a ‘good maker’.

How long does something like this take? It’s hard to quantify, but for some students the steps taken each year are huge, and for others they might change very little.

What are some of the biggest issues companies whom you consult for have with their operations and what are your solutions?

Interestingly many of the problems that people ask me for help with relate to timber technology and wood finishing issues. Whilst I’m not a wood scientist, timber technology has been a special interest of mine for many years, and people seem to have found out that I often know a bit more about wood than they do so they ask – the same with wood finishing.

Perhaps there’s a need for woodworkers to learn a bit more about the primary material they work with because I’m quite often taken aback by the elementary misconceptions that woodworkers have about wood. However, most of my consultancy work has tended to be in disputes between a supplier (maker) and a client concerning the quality of the work supplied, or I’ve occasionally been asked for my ‘expert’ opinion in legal disputes. Neither are areas of work that I feel it would be right to discuss in public.

You’ve had your work presented at several exhibitions through the years, has this been a great way to generate more business for yourself? How do you find most of your clients?

Exhibitions can be a double edged sword. They can generate interest, but I’ve never found them to be a major source of work. Currently most of my income comes from teaching, so I haven’t really pushed for clients for some time, although that might change in the future.

I exhibit work primarily for sale rather than generate further orders. The negative side of exhibiting I’ve found over the years is that exhibited furniture can experience all sorts of damage, some of it significant, which has to repaired by the maker at no charge. I’ve seen my furniture used as a display stand for all sorts of items, and scratchy bottomed pots slid around table and cabinet tops until the potter or gallery/exhibition manager has got it just the way they like come in for particularly vehement loathing on my part!